Weston Buckley Anderson (he/him)

Assistant Research Professor

University of Maryland, Department of Geographical Sciences

weston [at] umd.edu

Teaching Experience

Faculty – Climate and Society Master’s program, Columbia University

Dynamics of Climate Variability and Change (Fall 2020): co-taught with Dr. Alessandra Giannini

Threats to Urban Food Security (Spring 2021): reading seminar, co-taught with Dr. Cascade Tuholske

Teaching Assistant - Columbia University

Regional Climate Dynamics: Dr. Andrew Robertson and Dr. Pietro Ceccato (2016, 2018)

Dynamics of Climate: Dr. Ron Miller (2017)

Dynamics of Climate Variability and Change: Dr. Alessandra Giannini and Dr. Lisa Goddard (2017)

Guest Lecturer – Columbia University Irving Medical Center

Intro to Global and Population Health (2019, 2020)

Course Materials

Below are course descriptions for courses that I have taught, including the course objectives and course syllabus

GR5400 - Dynamics of Climate Variability & Climate Change

(Climate and Society Master’s Program, Columbia University)

This course provides an understanding of the physical workings of the climate system, and it underpins the goals of the rest of the C+S program. Building on that, students learn through lectures, readings, discussions and exercises, how to interpret climate information like forecasts and observational maps. We cover the physical and methodological basis of forecasts – from weather to climate change – as well as their uncertainties. Students are encouraged to critically assess the suitability of different types of climate information to answer questions of societal interest in discussion and within a group project. Given that climate variability acts on a number of time and space scales, which may be further influenced by man-made climate change, we also address how these aspects of the climate are realized, forecast, interpreted. Solid understanding of the physical system and appropriate usage of climate-related terminology will be emphasized throughout the course.

2020 Course Syllabus

Skills Developed:

Physical understanding of the climate system

Forecast interpretation

Climate literacy

Initial basis to determine suitability of information to society

Communication of scientific material

Earth Science Notes

Below are links to a set of notes that I’ve developed based on my own courses and study. These notes are a work in progress, and are not formal course material, but I have found them helpful and I hope you may as well. I have also included a set of useful papers under each topic.

Climate Dynamics

Many of these topics relate to those found under the atmospheric dynamics and ocean dynamics sections, so for specifics on ocean or atmosphere systems, see those pages.

Notes

Primitive equations

Vorticity

Geostrophy and Thermal Wind

Overview of the mean climate

Radiative Convective Equilibrium and the Greenhouse Effect

Overturning Circulations (Hadley and Ferrel cells)

Rossby Waves

The stratosphere (QBO and Brewer-Dobson)

The El Niño Southern Oscillation

Atlantic Climate (NAO and AMOC)

Papers

Robust Responses of the Hydrological Cycle to Global Warming (Held and Soden, 2006) – Held and Soden present an elegant argument as to why global patterns of P-E should intensify with global warming (‘wet get wetter’ hypothesis). The basis of their solution is that, over the ocean, specific humidity scales with Clausius-Clapeyron (7% 1/K) while precipitation/evaporation scale with changes in the Bowen ratio and net radiation (1-2% 1/K). Relative humidity is assumed constant with increasing temperatures (a fine assumption over the ocean, not over land). And while a decrease in the strength of the Hadley cell does somewhat offset this increased moisture (and therefore energy) content of air parcels, it does not do so completely such that there is an increased transport of water vapor by the Hadley cell (increased moisture convergence in the tropics, divergence in the subtropics): the wet-get-wetter and dry-get-drier.

A possible response of the atmospheric Hadley circulation to equatorial anomalies of ocean temperature (Bjerknes, 1966) – The classic paper in which Bjerknes describes the coupled ocean-atmosphere system that underpins the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). A key insight is how the mean state of the tropical Pacific ocean sets up the system to respond to zonal wind anomalies at the equator. A cessation of upwelling off the west coast of South America leads to warm sea surface temperatures, increased convection and thereby strengthening the westerly anomalies, which suppress upwelling.

The annual cycle in equatorial convection and sea surface temperature (Mitchell and Wallace, 1991) - In this paper Mitchell and Wallace detail how the ITCZ migrates over the course of the year. They show how the continental geometry sets up an asymmetry in sea surface temperatures with warm SSTs north of the equator and cold SSTs south of the equator. Stratocumulus decks then form over the cold SSTs to create a positive feedback, which helps the ITCZ persist north of the equator for longer than may otherwise be expected.

Some simple solutions for heat-induced tropical circulation (Gill, 1980) – Here Gill details the Matsuno‐Gill model for atmospheric response to localized tropical heating at the surface. I’ve included this paper here for its broad relevance in climate dynamics, not least of which relates to ENSO

A model El Niño-Southern Oscillation (Zebiak and Cane, 1987) – The first demonstration that key aspects of ENSO could be modeled in a simplified numerical context. Zebiak and Cane use their model to explore key mechanisms of the coupled system, the chaotic return time (with a preferred period of ~3-5 years), and the seasonal phase locking of ENSO. They find that a key aspect governing the strength of coupling in the system (and therefore the oscillation frequency and magnitude) is the upper ocean heat content, a buildup of which precedes warm ENSO events in their model.

Contribution of ocean overturning circulation to tropical rainfall peak in the Northern Hemisphere (Frierson et al., 2013) – Perhaps not a ‘classic’ paper, but certainly an elegant analysis that shows why the oceanic meridional overturning circulation is necessary in the dynamical balance that sets the ITCZ north of the equator. Frierson et al. note that the top of atmosphere insolation is equal in both hemispheres, but that the northern hemisphere has greater outgoing long wave radiation. And because atmospheric energy transport is southward, the northward transport of energy by the ocean is necessary for the annual mean ITCZ position to remain in the northern hemisphere.

Atmospheric Dynamics

Below are a series of notes that I’ve developed as teaching aides relevant for atmospheric sciences as well as a series of useful papers.

Notes

Overview of large scale atmospheric circulations

Greenhouse effect

Primitive equations

Vorticity

Geostrophy and Thermal Wind

Overturning Circulations (Hadley and Ferrel cells)

Rossby Waves

The stratosphere (QBO and Brewer-Dobson)

Papers

Subtropical Anticyclones and Summer Monsoons (Rodwell and Hoskins, 2000) – Rodwell and Hoskins characterize lower troposphere subtropical circulations. In the summer they characterize continental monsoons and oceanic anticyclones. Wintertime circulation is dominated by the zonally averaged circulation interacting with orography.

Nonlinear Axially Symmetric Circulations in a Nearly Inviscid Atmosphere (Held and Hou, 1980) – Held and Hou show how the annual-mean zonal-mean Hadley cell can be explained using conservation of momentum, thermal wind, and radiative convective equilibrium

An Overview of the North Atlantic Oscillation (Hurrell et al., 2003) – As the title implies, this article is an overview of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), including the dynamics, methods of calculating the index and potential implications for different sectors.

A Diagnosis of the seasonally and longitudinally varying midlatitude circulation response to global warming (Simpson et al., 2014) – This paper provides a more nuanced analysis of the often observed poleward-shift of the jet streams as a result of global warming. Simpson et al. find that that in the zonal mean the idea that high-frequency transient eddies will shift the midlatitude storm tracks (and jet streams) poleward is accurate. But in the Northern Hemisphere winter, modifications to stationary eddies tend to force a more complicated picture. The NH winter jet shifts equatorward in the east Pacific and strengthens over the Atlantic.

Ocean Dynamics

Although ocean dynamics is not my main focus, it is inseparable from climate dynamics as a whole. The topics and papers below are therefore chosen from the perspective of a climate scientist

Notes

Primitive equations

Vorticity

Geostrophy and Thermal Wind

The Wind-driven Circulation

Atlantic Climate (NAO and AMOC)

Papers

Wind-driven currents in a baroclinic ocean; with application to the equatorial currents of the eastern Pacific – (Sverdup, 1947) – Here Sverdrup demonstrates how wind-driven currents lead to the mean-state ocean circulations such as the equatorial countercurrent, which flows eastward against the trade winds.

Biogeoscience

As a climate scientist I am no expert on agronomy or plant physiology, but as a scientist working on how climate variability affects food security it’s important to understand how the climate affects vegetation, and how vegetation may in turn influence the climate. Below are a brief set of notes covering topics such as plant-water relations, nutrient cycling, the influence of rising CO2 on vegetation and how large-scale dynamics may affect large-scale vegetation patterns.

Notes

Plant Ecophysiology

Terrestrial Ecology

Global Agriculture

Statistics/Math

Climate science often relies on statistical and mathematical techniques to diagnose changes in the climate system. These techniques become particularly relevant as the prevalence of large ensembles of model simulations increases. The topics covered below are in no way representative of the available tools used in data analysis, but rather a brief list of some of the most common tools used in climate science.

Notes

Basics (Statistical moments, least squares, auto-covariance)

Models and model fit (linear, nonlinear, nonparametric)

Fourier transforms and power spectra

Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) and Empirical Orthogonal Functions (EOFs)

Bootstrapping (conventional and phase randomization)

Papers

An Intercomparison of Methods for Finding Coupled Patterns in Climate Data (Bretherton et al., 1992) – Bretherton and his coauthors discuss the relative merits of different methods used to extract modes of variability from noisy data. They focus on principal component analysis (PCA), canonical correlation analysis (CCA), and singular value decomposition of a covariance matrix (SVD). This is a classic paper for understanding the tools that are often used in climate science and their potential limitations

Detecting Causality in Complex Ecosystems (Sugihara et al., 2012) – Sugihara and colleagues outline what Lorenz attractors are, and how they can be used to make predictions in coupled, non-linear, chaotic systems. They include links to some videos explaining the material that are tremendously helpful

Outreach

Climate-based creative writing prompt

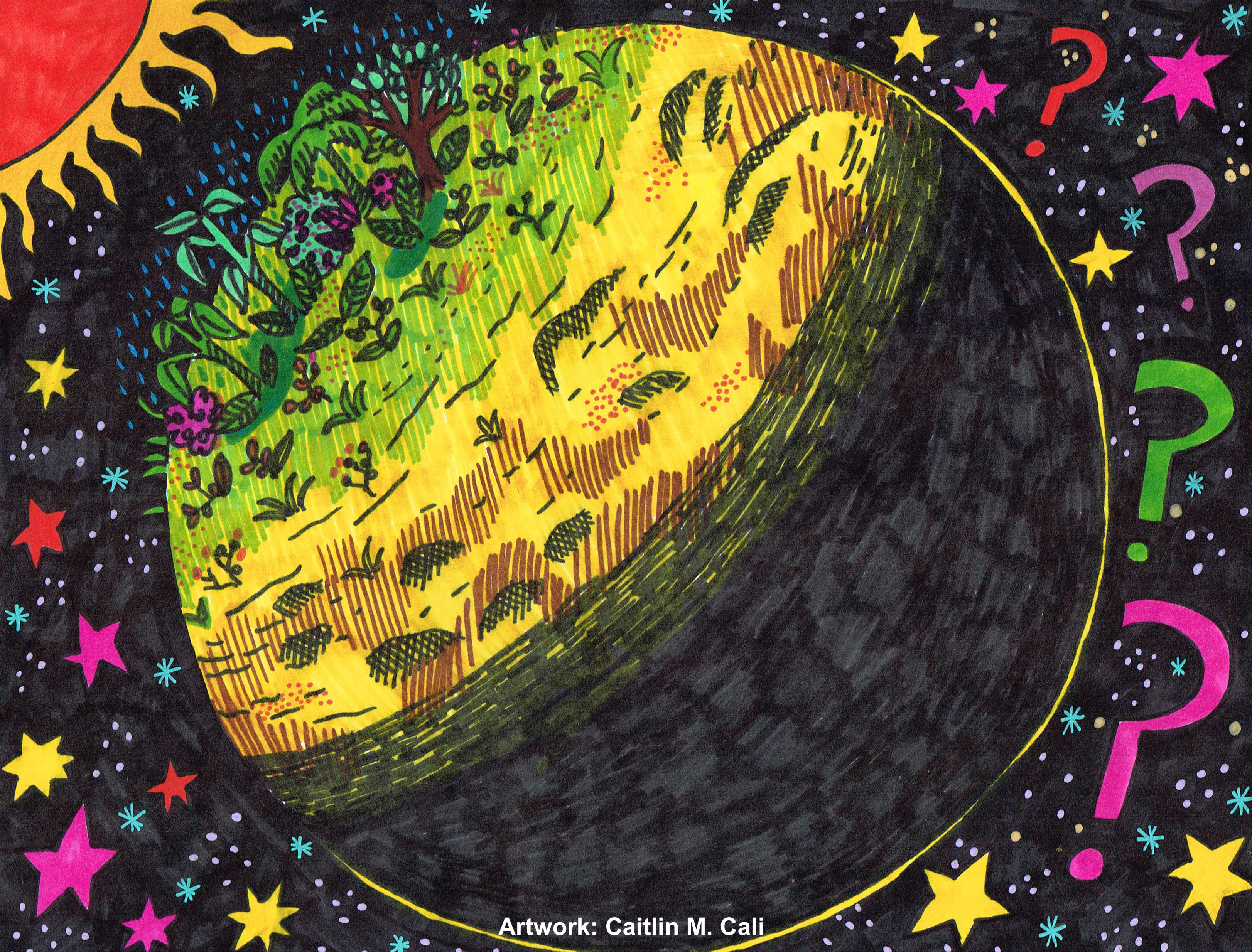

Below is an artists’ rendition of a tidally-locked planet, you can also follow this link to a video describing the tidally-locked planet, and asking K-6 students to write about characters that would inhabit such a planet. The idea is to discuss how our climate could be different and to describe those environments in-depth. For college-level students, the artists rendition can be combined with the first-principles understnading and the climate simulations of Merlis and Schnider (2010) in an activity in which students are provided the constraints of negligible rotation and the location of insolation maximum, then based on first-principles students work in groups to describe the main climate-features of such a planet before coming back together as a class to discuss their solutions and those of Merlis and Schnider